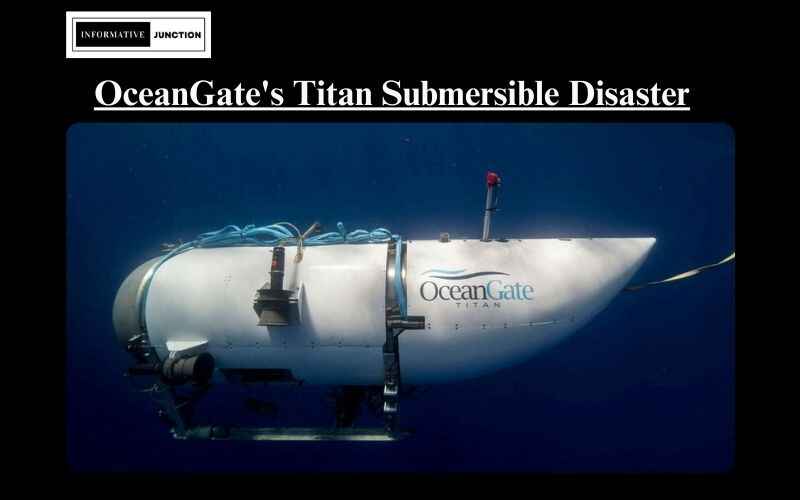

While the OceanGate Submersible Failure was seen as salvageable by some, experts on the subject knew it was doomed from the start. The engineering errors that contributed to the loss of life in the OceanGate Titan submersible, a project of OceanGate Inc, will be discussed in this article.

The New York Times said that “OceanGate faced several warnings as it prepared for its hallmark mission of taking wealthy passengers to tour the Titanic’s wreckage” in the years before its submersible craft vanished in the Atlantic Ocean with five people aboard.

The OceanGate Deep-Diving Rover

It would have been difficult to escape coverage of the OceanGate submersible if you have access to a smartphone, TV, or computer. After 105 minutes of deployment, communications were lost, and the ship was never seen again.

Since its inception in 2009, OceanGate has been an industry leader in manned submersible development. The company’s goal is to make the underwater environment more accessible to scholars, explorers, and private sector so that they may study it and keep an eye on it.

The French inventor Jules Verne is credited with creating the first functional submersible in the early 20th century. Several major disasters, such the loss of the Kursk in 2000 and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, have used submersibles since then. Tragedies like the one at OceanGate are painful reminders of the perils involved with underwater exploration and the critical importance of strict safety measures.

Despite the tragic loss of the Titanic submersible, OceanGate has completed a number of successful trips in the past. Some examples are the Andrea Doria dive and the SS Governor dive.

There were frantic efforts to find and save the submersible after it disappeared. A large fleet of ships searched for any audible clues. When reports of pounding came in, it became more urgent to locate the submersible in order to rescue the crew before they ran out of oxygen.

The discovery of wreckage on the ocean below, only a few hundred meters from where the Titanic had sunk, converted hope into dread. The rudder assembly was the first part of the submersible to be discovered. As time passed, it was obvious that the submersible had crashed. Industry insiders understood the submersible had likely exploded when communications were lost, but the media and millions of viewers were under the impression that the crew could have lasted for several days.

If the Titan submarine had failed, it would have ended everyone’s suffering quickly and mercifully. Titanic-like pressures would have caused an implosion in a matter of milliseconds. The submersible would have been destroyed by water traveling at a speed of about 600m/s, or roughly double the speed of sound. Anything within, including the crew, would have been instantaneously reduced to ash due to the high internal temperature created by the rapid compression of the air. Plunger-style fire starters are a good way to witness this phenomenon in action.

Once an impressive feat of modern engineering, the ship is now a smoldering wreck. The ocean’s cruel depths sucked everything down and now all that is left is an eerie void and a trail of unanswered questions. The crew, on a mission of discovery and exploration, was destroyed by forces beyond their control.

How the Ocean Gate Submersible Was Designed

This section will investigate the submersible engineering problems that contributed to the OceanGate incident. Examining the engineering, or lack thereof, of the OceanGate submersible can shed light on the ship’s demise. While the Titanic mission ultimately failed, OceanGate did make important advancements in the field of oceanography. They took a fresh approach to submersible technology that has allowed for new avenues of ocean exploration and discovery. As tragic as the Titanic expedition was, it highlights the need for strict safety regulations and expert oversight in endeavors of this magnitude.

Parts designed for harsh environments are typically more expensive, but any competent engineer knows there is a valid reason for that. In order for automobiles to provide both reliability and safety, it is essential that automotive-grade parts can withstand vibration and extreme temperature changes. Medical implant components must be inert to living tissue, and those used in aerospace vehicles must be able to resist low pressures and high altitudes without outgassing and failing.

A flaw in a structure housing a low-pressure environment (such as air at one atmosphere of pressure) can swiftly cause the structure to collapse and crush anything inside the ocean’s depths due to the enormous pressures present there. A 1 cubic meter of gas at 1 atmosphere pressure, for instance, would be compressed to a 1/300 smaller volume at pressures of 300 atmospheres.

Engineers must guarantee that all submerged components not only can endure but also significantly exceed certain pressures for optimal safety. Because of the potential for catastrophic implosions, submersibles are typically built with spherical shapes, strong controls, many redundancies, and several safety precautions.

What therefore, did the OceanGate have built into it so that it could function at such depths? According to the circulating sources, it appears not at all.

Carbon Fiber Hulls: A Risky Option

Almost all submersibles are made out of steel or other solid materials because they are homogeneous, meaning that their qualities are consistent in all directions. Since a solid material behaves the same from all sides, it is quite simple to simulate the forces it encounters under any given pressure.

Unfortunately, the OceanGate submersible used a carbon-fiber cylinder, which is not only an ungainly shape but also, in contrast to steel, not a uniform material. Because it is made up of individual fibers, carbon fiber has directional strengths and weaknesses.

The CEO of OceanGate, Stockton Rush, recently dropped the bombshell that the hull of the company’s Titan submersible was constructed using carbon fiber from a decommissioned Boeing airplane. The Mirror said that Rush had purchased the carbon fiber from Boeing at a “big discount” because of the material’s long-past expiration date for use in airplanes. This calls into question the safety of the Titan’s building materials and the crew’s ability to trust in them.

According to reports, OceanGate employed carbon fiber that had come from Boeing but had expired, rendering it unsuitable for use in aerospace. It is plausible, then, that the source of the breakdown was an ancient material with irregular qualities that had been shaped in a way that was never meant to withstand the extreme pressures found in high-pressure settings.

Let me define a few terminology to help you wrap your head around the technicalities. Unlike a submarine, which often emerges for air, submersibles are designed to stay submerged for long periods of time. Carbon fiber is a lightweight and durable material with many applications in the aerospace and automotive industries. However, it is not ideal for all uses because its strength changes with the direction of force. Steel and other “homogenous materials” are simpler to understand and anticipate the behavior of under pressure because their properties are uniform in all directions.

For what reasons was carbon fiber a bad option?

Examining carbon fiber’s characteristics can help clarify why it was a bad option for the submersible’s hull. As a composite, carbon fiber combines the benefits of multiple materials while minimizing the drawbacks of each. These components include carbon atoms and a binding polymer in carbon fiber. Although carbon fiber has a reputation for being lightweight and strong, these characteristics may not hold true in all directions. Because the carbon atoms are aligned down the length of the fibre, the material is robust in that direction but brittle in all others. Carbon fiber is less desirable for use in situations that call for homogeneous strength, such as a submersible hull that must endure strong pressures in all directions, due to its anisotropic nature.

Carbon fiber is inappropriate for use in submarine hulls due to its:

- Carbon fiber has strong strength along the fibre’s direction but lower strength in other directions, a property known as its anisotropic strength.

- Carbon fiber’s strength can change with the direction of an applied force, due to the material’s non-uniform properties.

- Carbon fiber’s strength and durability degrade with age, especially when its use-by date has passed.

The Mirror: Myopic Decisions

The OceanGate submersible included a little window at the front through which the crew could observe the water. Although many submersibles have similar windows, the one used by the OceanGate sub reportedly could not be utilized below 1,300 meters (source: New York Times). Considering the Titanic is submerged at a depth of four thousand meters, the viewport presents a safety risk. A factor of 4 is a significant margin above the viewport’s stated rating, even if the created rating would have been substantially lower than the genuine rating.

The Problem with the Entry Point: Being Locked In

Titanium, which is likely sufficient for the depths involved, was chosen to construct the dome that contained the front viewport. The single way in and out of the submersible, the front dome, is bolted shut from the outside, which has led some to wonder about escape routes in case of an emergency. The only way out is for engineers on the outside to come in and unbolt the dome in the event of an emergency.

For a deep-sea dive, this is not a problem (because opening the hatch would be insane), but problems at the surface would effectively cage the crew. Everyone with even a passing familiarity with the submersible industry knows how crucial it is to have escape hatches.

Finally, the usage of an epoxy resin is suggested by video footage demonstrating the sealing process between the spheres and the carbon-fiber cylinder. Epoxy resin can develop cracks as a result of pressure and temperature fluctuations, and it is unclear whether or not this has been rated. Another potential point of failure is the presence of minute air bubbles and breaches in the resin seal, which could be overlooked if X-ray devices were not used to inspect the vessel (as is typical practice for vessels of this type).

Toy for Kids: Controlling the Ocean Gate

The media has regularly criticized the game’s design, specifically its reliance on a single Logitech F710 gaming controller. Some have countered that game controllers are used in a wide variety of other contexts, including the military. However, the reality is that even in these contexts, game controllers are manufactured to a considerably higher quality. There are also supplementary controls that are much more powerful and can be used in place of a game controller.

A game controller could be beneficial in the case of submersibles for either allowing tourists to control the craft once they arrive at their destination or for panning cameras operated by tourists. However, such a controller would never serve as the primary means of control, as backup systems would always be in place.

The OceanGate submarine was already problematic due to its wireless Bluetooth controller. Engineers that have worked with Bluetooth are well aware of the technology’s reliability issues. It would not take much for the controller’s commands to be misunderstood, or even worse, for the controller to be forcibly reconnected and lose control at a crucial point.

Using Ready-Made Parts Is Just a Waste of Money.

The underwater vehicle was equipped with a number of displays and lighting systems. The CEO of OceanGate said in interviews that the company bought several of these parts, including the lighting, at a local camping store. While it is possible the interior setting might support such gear, any worries about security raise doubts about whether or not they were the best option.

When Young Engineers Replace Older Ones, History Always Repeats Itself

Instead of hiring more seasoned engineers, Ocean Gate’s CEO chose for a younger team to create the Ocean Gate Titan. This choice may have been motivated by a search for novel viewpoints, but the absence of seasoned engineers with decades of expertise may have contributed to the difficulties encountered.

There is certainly nothing wrong with hiring inexperienced engineers — after all, everyone has to start somewhere — but in safety-critical applications, it is always important to have at least one or two seasoned veterans on staff. Younger engineers may suggest novel approaches and techniques that more seasoned engineers overlook, but the latter’s years of service guarantee a level of care and caution that their inexperienced counterparts lack.

The New York Times claims that OceanGate was informed of the “catastrophic” risks associated with the Titanic mission. Many professionals, both inside and outside of OceanGate, warned of the risks involved in the endeavor and urged the organization to get certified. The firm ignored these warnings and went ahead with their preparations, which ultimately resulted in the Titan and her crew perish.

What the Coast Guard Found

As a result of the terrible event, the U.S. The Titan submersible and its crew went missing, prompting the Coast Guard to launch an investigation into the tragedy. Titan submersible debris was found on the ocean floor about 500 meters from the Titanic’s bow. Since the MBI is the Coast Guard’s highest level of investigation, it is responsible for figuring out what went wrong, if any misconduct, incompetence, negligence, unskillfulness, or intentional lawbreaking played a role, and if any new regulations or statutes are needed to prevent a similar tragedy from happening again.

Why Bad Engineering Is Deadly

The effects of shoddy engineering, as demonstrated by the OceanGate scandal, will be discussed here. From its construction to its technology, the OceanGate submersible was a failure. Five lives were lost due to a lack of preparation, shortcuts used, and an unwillingness to get accreditation.

The Titan submersible was seen in a new light by Arnie Weissmann, editor-in-chief of Travel Weekly. The weather prevented him from ever taking a ride in the Titan, but he spent a week on its support ship and got a front-row seat to the action. Weissmann recounted speaking with OceanGate Expeditions’ CEO Stockton Rush, who assured him the Titan’s hull was safe despite being constructed from carbon fiber that had been heavily discounted after its useful life in airplanes had expired. Rush is both a thorough planner and team leader, as pointed out by Weissmann, and a cocky, self-assured pioneer. Weissmann now thinks that Rush’s major weakness was that he was overconfident in his own abilities as an engineer and saw himself as a pioneer.

Following correct engineering procedures and investing in safety is crucial to the success of any project, as demonstrated by this occurrence. The CEO of OceanGate felt that the submersible community was being overdramatic in their complaints about their design and that safety precautions were restrictive and unneeded.

As unfortunate as it may be for the rest of the neighborhood, the CEO was, and remains, 100% correct. The implosion of the submersible would have happened so quickly that he never would have had time to realize his mistake.

After the OceanGate submersible failed, inquiries were opened to ascertain what went wrong. The tragedy highlighted the need of safety precautions and the risks associated with exploring new territory.

Connect with Informative Junction

Click Here if you want to read more Interesting Blogs.